Quill looks like the latest “embedded SQL DSL” for Scala, and so far I think it looks fairly compelling:

case class Person(name: String, age: Int)

val q = quote {

query[Person].filter { _.name == "John" }.map { _.age }

}

// SELECT age FROM person WHERE name = 'John'

testDb.run(q)

They even have compile-time validation of your queries against the database.

E.g. if you typo the Person.age field in the case class as agee (note the extra e), there will be a testDb.run compilation error, with error text from the MySQL database itself, where Quill tried to execute the query and it failed.

(Although, for this specific feature, I wonder how having random queries executed against your database would mess with your local test data; e.g. AFAICT the query is actually executed during compilation, which I suppose means having two local databases: one for test data/selenium/unit tests, and one for Quill.)

My biggest angst about query DSLs is that I think it’s hard for them to support truly everything you’d want to do in a database query, and so you will always need an escape hatch down to raw SQL. E.g. this is the case for Joist’s DSL, albeit it is much more amateur than Quill.

However, Quill looks like it could handle most queries in an intuitive/non-surprising manner.

If it could, then Quill looks like a potential/intriguing abstraction for my mused “holy grail of database testing”: to not use the database at all.

E.g. in a typical project setup, I like to break the tests up into groups:

- Pure in-memory tests, e.g. validation that only works against the in-memory domain objects/input themselves.

- Domain database tests, which commit domain objects all the way to the database.

- These can also be process tests, which are typically background/batch jobs that inherently use multiple transactions/Units of Work

- Selenium tests.

The run time for these quickly goes: 1) blazingly fast, 2) basically good, 3) horrible.

The large caveat for group 2, domain database tests, is that they typically run fast enough individually, but can take awhile in aggregate.

E.g. for Joist, Joist will generate a flush_test_database stored procedure that TRUNCATEs all entity tables in your database (only locally, not in production of course). You can then issue 1 JDBC query before each test method to reset your database, then setup your new test-specific data, and each test method can run in ~0.1 seconds (assuming you have your local database’s fsync/etc. disabled). E.g.:

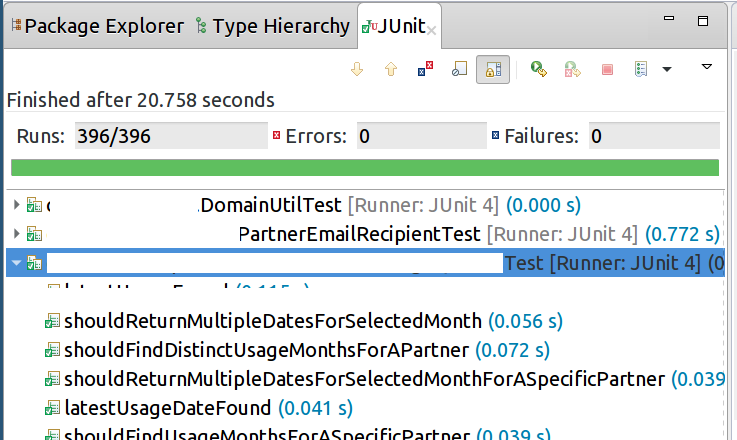

400 database tests in 20 seconds is pretty good.

In fact, for database tests, I think it’s basically good enough, in that I haven’t spent time trying to optimize it more than this. (Although I did have to downgrade to MySQL 5.5, as TRUNCATE is order of magnitudes slower in MySQL 5.6 and 5.7, which a topic for another blog post.)

Nonetheless, let’s say we did want to get faster than ~0.1 seconds/database test, and approach in the speed of in-memory tests, say an order of magnitude faster, like ~0.01 seconds/test.

I think the only way to do that is stay entirely in-process (e.g. we can talk about in-RAM/ramdisk MySQL/H2/etc., but I think anything that involves JDBC touching a socket is going to hit a ~10ths of a second order of magnitude).

So something entirely in-process might look something like:

- Have a

Repositoryinterface that can do basic persistence, e.g.load(Domain.class, id),save(domainInstance) - Objects are not serialized to any on-disk/other store, instead are kept in basic collections (this is for testing only, so no on-disk safety is needed or even wanted)

- Each

load(Domain.class, id)just returns the object directly, albeit a copied version

- To maintain the facade of database ACID, we still need “transactions”, but that can be a giant

synchronizedblock around each Unit of Work - Queries can be run via

Repository.query(Query)and are evaluated directly against the in-memory objects/collections

- This is where Quill comes in, as historically there hasn’t been a sufficiently decoupled query language. You could use SQL itself, and somehow write a SQL parser than eval’d against in-memory objects, but then you’re still going through the JDBC stack, and I think one of the potential speedups is to avoid

PreparedStatement,ResultSet, etc., that all together and just take Quill’s (or equivalent’s) AST directly

So, that is the holy grail. Obviously I think it would be a lot of infrastructure work, because you’d need to get the whole stack to a point where you really trust it. E.g. if the in-ram tests passed, but you still felt like you had to execute it against the database to “make sure it really works”, when it would not be a useful abstraction. Too leaky and what not.

But if you can trust it, e.g. that the (framework-provided) InMemoryRepository has 100% of the same semantics as the (also framework-provided) ActualJdbcRepository, then you can remove it from the code you need to test, and focus solely on your domain/process logic. And if it works against the InMemoryRepository, you can assume it works against the ActualJdbcRepository.

(Tangentially, a Repository interface that has JDBC and in-memory implementations, e.g. JdbcEmployeeRepository and RamEmployeeRepository, is an old-school technique in Domain Driven Design. However, the approaches I’ve always seen involved hand-coded implementations of JdbcEmployeeRepository.findByName that uses SQL, and a RamEmployeeRepository.findByName that uses Java code, which I think is a) wasteful by having to write two method implementations of the same logic, and b) doesn’t actually solve the database-abstraction problem, because I really want the SQL-using findByName tested anyway. Also, the RamEmployeeRepository implementations rarely obey ACID/etc. semantics that are exactly needed by the cross-Unit Of Work domain/process tests that we weren’t able to test purely in RAM.)

(Also tangentially, this framework-provided “trusted abstraction of an expensive dependency” is the main feature of Tessell, which provides “implementations you can trust” of both in-memory and then browser-coupled DOM elements/GWT widgets, so that you can run your presenters against the in-memory version (stubs), and then trust it will work the same against the browser versions. And, if you accept this trust, your tests can run much, much faster. Granted, Tessell cheats a bit by not providing any rendering-level logic, e.g. pixel offsets/etc., that are thankfully rare to need in presenters themselves.)

So, anyway, if I were to embark on a Quixote-like quest for a next-generation ORM, that I knew was going to be used in a “100s to 1000s”-entity enterprise software project, that is the approach I would attempt.

(I think enterprise projects are interesting, in that the focus is different from startups: in my experience, startups typically have simpler domains, with relatively few total entities, but the novelty is on raw volume (“Internet scale” and what not), where as enterprises typically have much larger, more complex domains, perhaps due to the maturity, or just age/cruft, of their business models. So the success of the enterprise project, over the long term, is less about production-time concerns like raw volume/throughput, and more on just managing the developer-time complexity, e.g. not ending up with a tangled mess. As a very concrete example, a startup could hand-code their persistence layer of ~10-50 entities, but this would be a nightmare for a ~500-1000-entity enterprise code base.)